What makes a system distributed that a multiprocessor is not?

What is a distributed system? Every definition I’ve ever come across always has me eventually realizing “wait a second… this also applies to multiprocessors!”. The goal of this article is to have fun analyzing multicore and distributed computing, and realize that they might not be as qualitatively different as people make them out to be.

- True but Useless Definitions

- Meaningful Difference is Quantitative: Latency

- Debunked Definitions that also apply to Multiprocessors

- Conclusion: Consistency Models Hierarchy

True but Useless Definitions

Let’s start with a bittersweet conclusion: the only definitions of distributed systems that are not debunkable are those that are generic enough to not be very useful in practice!

I’ve found two thus far:

A distributed system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable. – Leslie Lamport

So a distributed system requires at least two separate boxes, one of which depends on the other. Hard to argue that a multiprocessor computer fits in this definition, sure, but it’s also not a very useful definition to build a theory, abstractions, or reusable components out of.

Distributed computing is a computational paradigm in which local action taken by processes on the basis of locally-available information has the potential to alter some global state. – Some HN citizen

This one uses “process” instead of “computer”, so a multiprocessor computer would fit this definition!

What then, is the difference between a concurrent program running multiple processes on a multiprocessor vs having those processes run on separate boxes?

Meaningful Difference is Quantitative: Latency

It’s the Latency, Stupid – Stuart Cheshire

There’s one physical constant that applies to all systems uniformly and mercilessly: the speed of light.

This makes for a very important quantitative difference between various systems: how far different components are from each other puts a lower bound on the latency of the system.

Indeed, apart from latency, notice how close a single machine is to a typical backend:

CPU(s) -> RAM -> Disk

Web server(s) -> Memcached -> DB

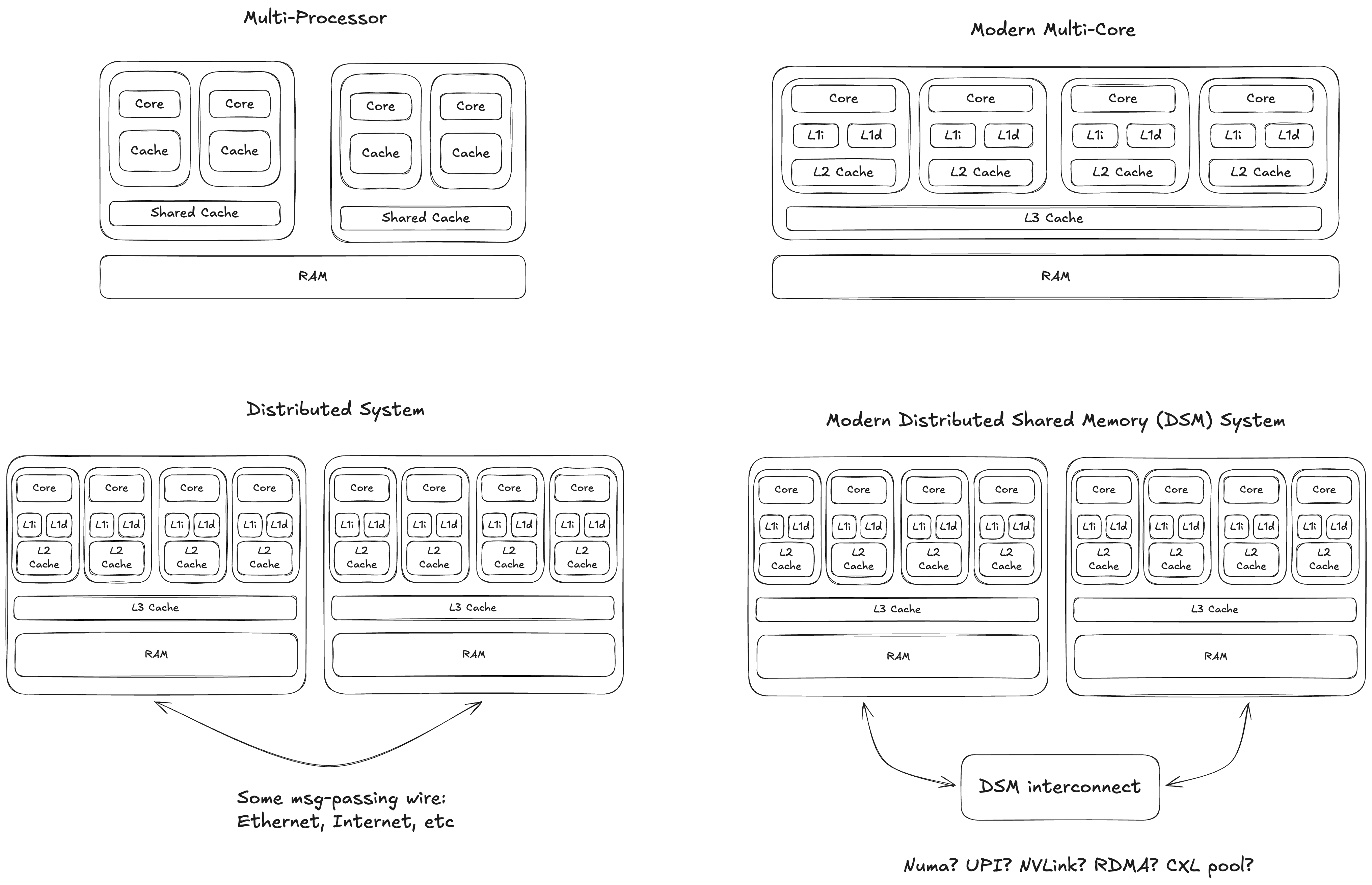

And just as the divide between multi-processors and single processors with multiple cores has blurred over time with technologies such as chiplets, so is the divide between single machine and multi-machine also blurring, at least inside datacenters, with technologies like CXL and RDMA.

Debunked Definitions that also apply to Multiprocessors

I have looked around for more specific definitions/classifications of distributed systems, and have not found a single one that doesn’t also apply to multiprocessors.

Qualitative Difference: Partial Failures & Impossibility Results

Seasoned distributed system engineers will be quick to retort: “It’s not just the latency; it’s the unreliable components and their partial failures”, and begin to cite a million theorems and acronyms:

- Two Generals Problem

- Byzantine Generals’ Problem

- The Network is Unreliable

- FLP Theorem

- CAP Theorem

- … yawn …

- A Hundred Impossibility Proofs for Distributed Computing 🫳🏼🎤

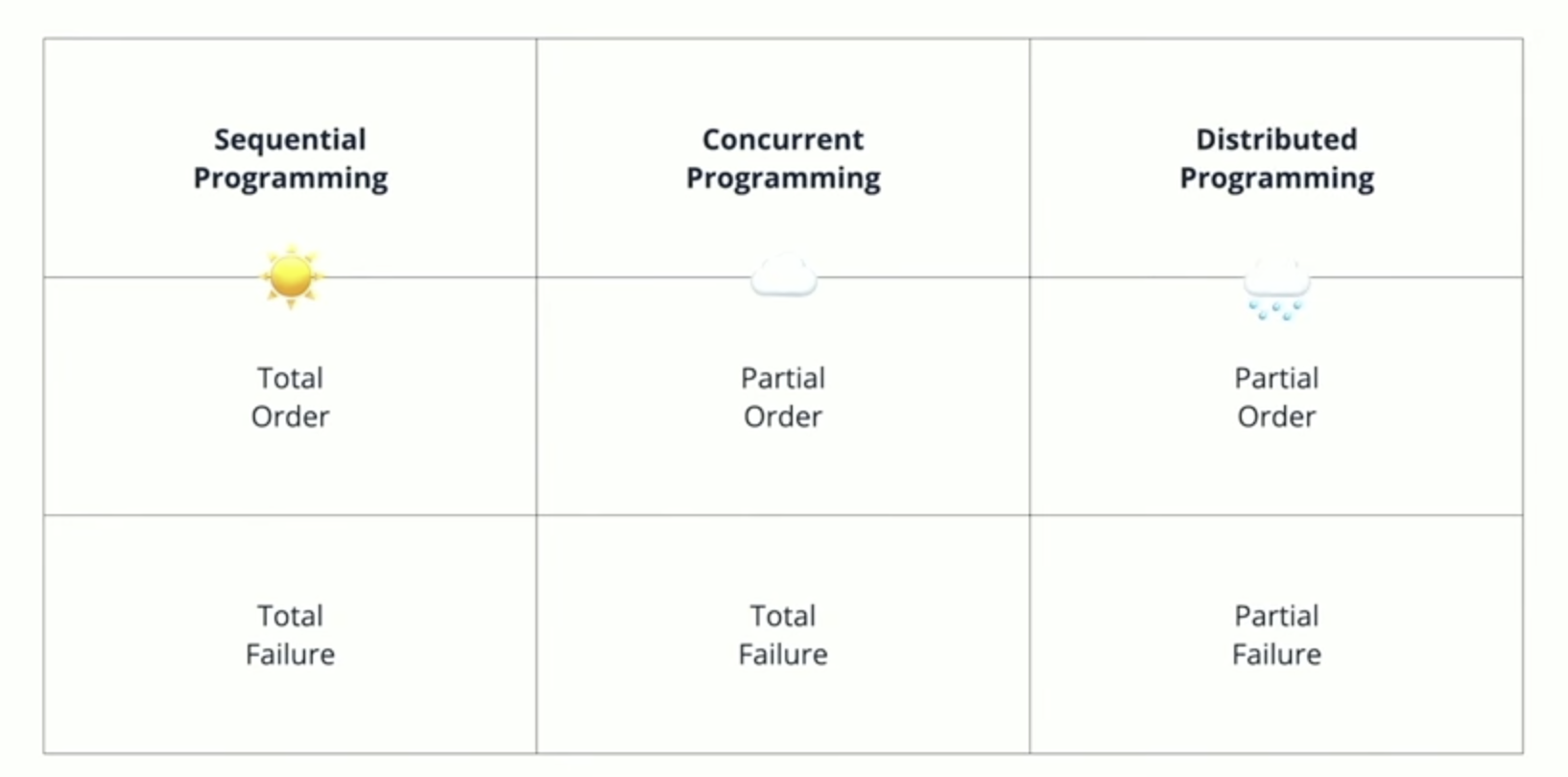

Indeed, partial failures is how Dominik Tornow distinguishes concurrent programming from distributed programming in his Distributed Async Await presentation:

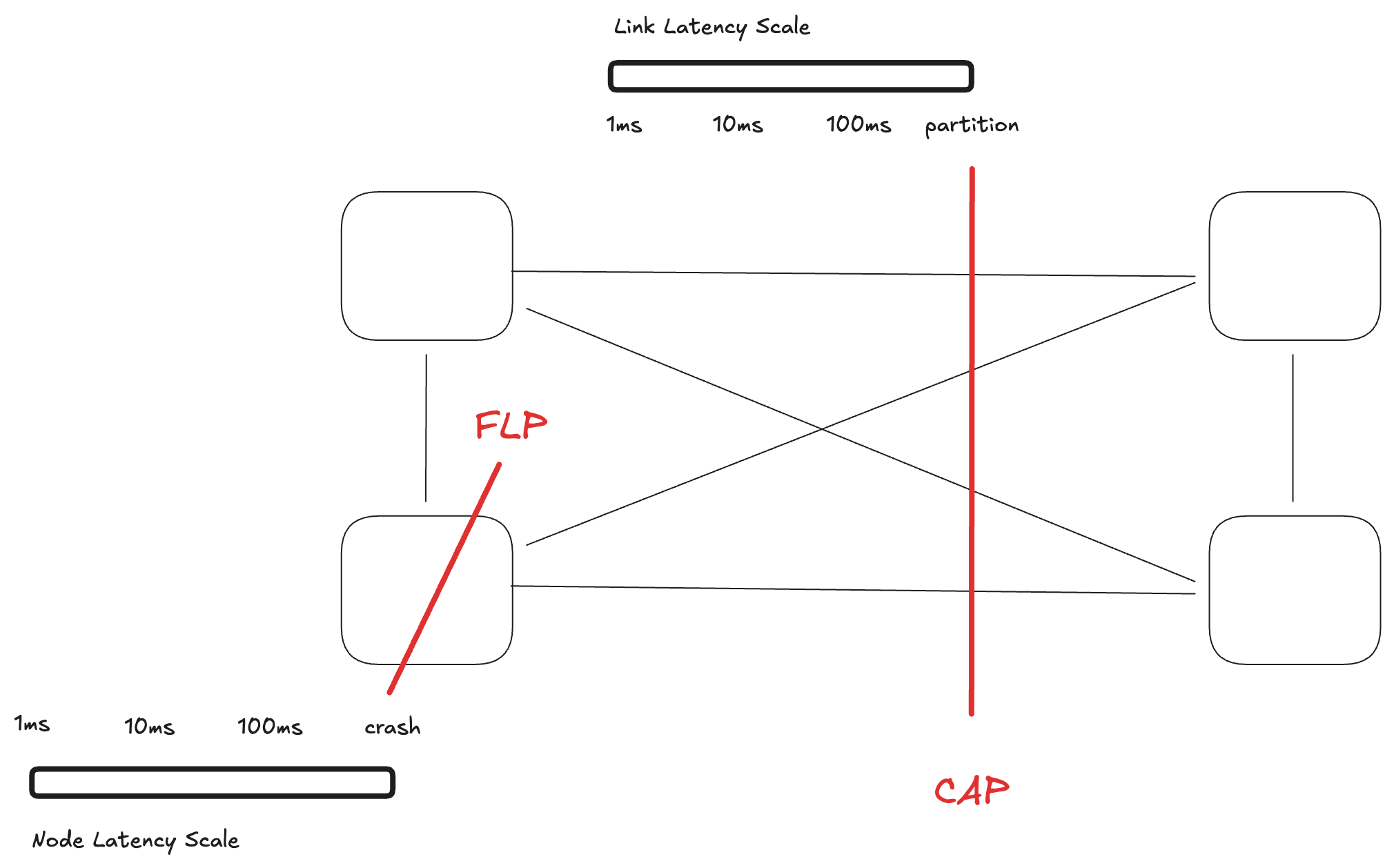

The claim is that the main difficulty when dealing with distributed systems is that nodes may crash and wires may be cut, and that it is very hard to know which of those is the culprit, or if your packets are just slow, stuck in some router’s bufferbloated queue. The FLP paper starts with:

The consensus problem involves an asynchronous system of processes, some of which may be unreliable. The problem is for the reliable processes to agree on a binary value.

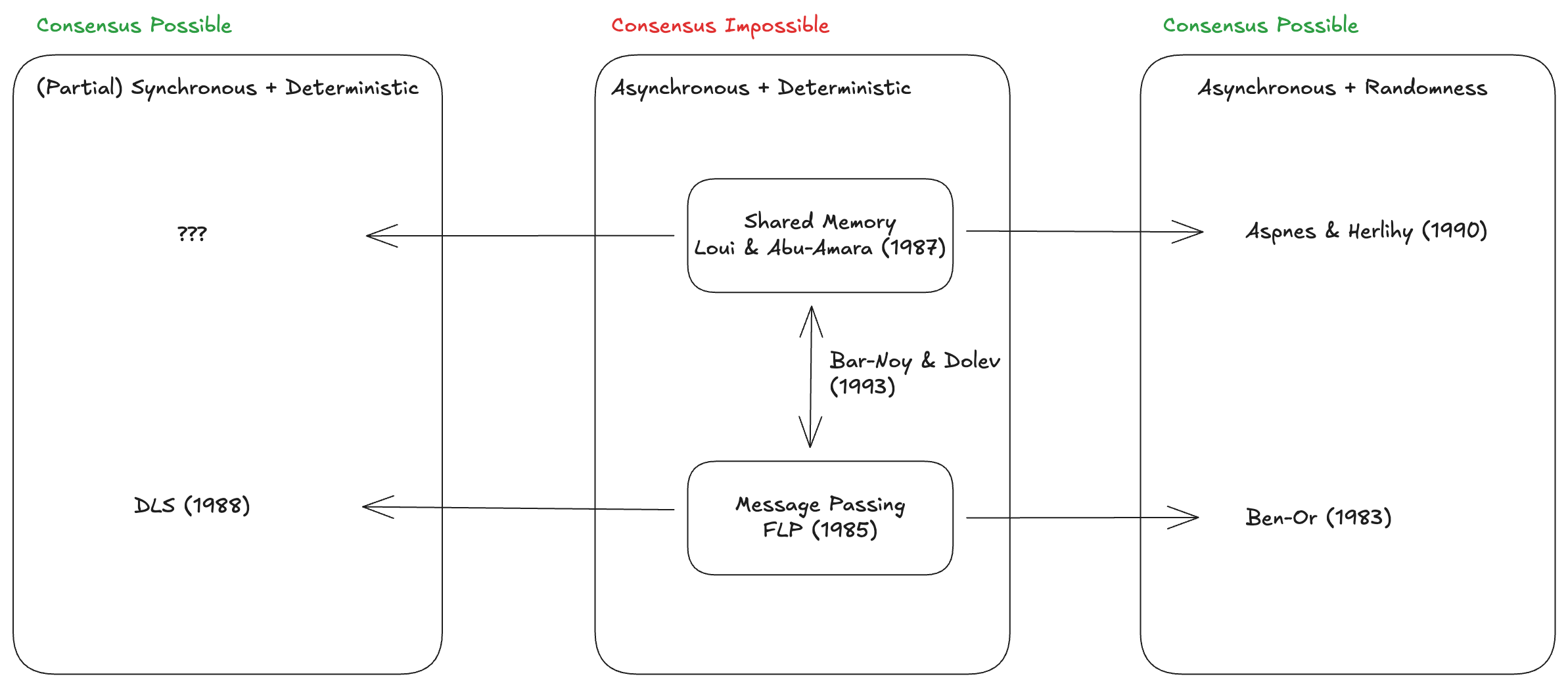

Unreliability indeed sounds like a qualitative issue, but notice how it’s paired with asynchronicity. What is asynchronicity if not latency…? If FLP can’t distinguish slow from crashed, that also means it can’t distinguish “a little slow” from “extremely slow”!

It’s always quantitative, dummy! Note how if you squint strong enough, the FLP and CAP theorems blend together (and hence shouldn’t be a surprise that they appear next to each other in the consensus cheatsheet). CAP applies to partitioned (read infinite latency) network without node crashes, whereas FLP applies to a reliable but slow (asynchronous) network with at least one node failure. Now replace partition with 2 hour delivery delay, or node crash with 2 hour GC pauses, and you might just read FCALPP.

Of course, I am speaking extremely informally here; the two theorems apply in extremely precise mathematically defined settings. However, this theoretical restriction is also the reason why Martin Kleppmann jokes that CAP is Crap, Marc Brooker calls CAP irrelevant, and that the FLP can be beaten with a little bit of randomness (… and binding). In fact, there’s even a quantitative generalization of the CAP theorem, called the CAL theorem, formalizing the intuition behind the PACELC principle.

Getting back to our definition that a system is distributed if it suffers from partial failures, we should already have the intuition that binary partial failures are not the real culprit; slow and unreliable responses is. And the main point is that while slowdowns and partial failures are clearly more common at scale, they do also appear on single boxes:

- Hyperscalers suffer from mercurial cores and unreliable RAM

- Working in a plane at high altitude greatly increases the chances of a RAM bit flip happening; and your laptop likely doesn’t have ECC memory

- Asynchrony is also absolutely possible on single boxes due to unfair (non-RTOS) schedulers, or language runtimes that can have very long GC pauses!

| Failure Type | Multicore | Distributed |

|---|---|---|

| Process crashes | Kills whole program (but threads crashing can silently corrupt memory!) | Independent Failures |

| Link failures | Rare (hardware fault) | Common (network issues) |

| Byzantine faults | Very rare (hacker) | More common |

| Correlated failures | High (power, kernel) | Lower (independent) |

| Partial Failures | Uncommon | The norm |

In conclusion, according to the definition that uses partial failures, a multiprocessor computer is also a distributed system.

Tanenbaum’s Classification

Let’s try another one. Wikipedia, quoting from Tanenbaum’s textbook, states:

Three challenges of distributed systems are: maintaining concurrency of components, overcoming the lack of a global clock, and managing the independent failure of components.

Let’s break these down one by one.

1. Concurrency

Multicore computers already deal with concurrency, parallelism and partial order, as we saw in Tornow’s diagram above, so this is not specific to distributed systems.

2. Lack of a global clock

Without getting into the details of how physical clocks work, here’s a diagram showing how apps use libraries that interact with one of the POSIX clocks, which itself relies on some hardware counter.

Application Level (TigerBeetle's view):

├─ Monotonic Time (intervals)

├─ Wall Clock Time (human timestamps)

└─ Logical/Hybrid Time (distributed ordering)

↑

Kernel Clock Types:

├─ CLOCK_REALTIME (wall clock)

├─ CLOCK_MONOTONIC (since boot)

├─ CLOCK_MONOTONIC_RAW (no NTP)

└─ CLOCK_BOOTTIME (includes suspend)

↑

Kernel Clocksources (hardware):

├─ TSC (CPU counter; best)

├─ HPET (chipset timer)

├─ ACPI PM Timer

└─ PIT (legacy)

Time Stamp Counter (TSC) is the most accurate source available on most desktops, yet as Wikipedia states:

The Time Stamp Counter was once a high-resolution, low-overhead way for a program to get CPU timing information. With the advent of multi-core/hyper-threaded CPUs, systems with multiple CPUs, and hibernating operating systems, the TSC cannot be relied upon to provide accurate results — unless great care is taken to correct the possible flaws: rate of tick and whether all cores (processors) have identical values in their time-keeping registers. There is no promise that the timestamp counters of multiple CPUs on a single motherboard will be synchronized. Therefore, a program can get reliable results only by limiting itself to run on one specific CPU. Even then, the CPU speed may change because of power-saving measures taken by the OS or BIOS, or the system may be hibernated and later resumed, resetting the TSC. In those latter cases, to stay relevant, the program must re-calibrate the counter periodically.

Again we see that multiprocessors could qualify as distributed systems here, and that the main difference between them and distributed systems is… quantitative! It’s always about the latency; and clock synchronization is no different.

NUMA nodes can stay below 1us accuracy. On small distances with hardware timestamping, PTP can get down to 10-100us accuracy. Even inside modern datacenters, since the advent of Google Spanner’s TrueTime API, GPS antennas and atomic clocks are able to offer APIs that return error bounds on the order of <10ms.

3. Independent failure of components

As we’ve seen in the previous definition, partial failures on single machines do exist: see ECC-RAM and mercurial cores.

8 Fallacies of Distributed Computing

The fallacies of distributed computing are an informal characterization of distributed systems from the 1990s. Readers won’t be surprised at this point to learn that multicore systems suffer from the same 8 fallacies:

1. The network is reliable

2. Latency is zero

Cache hierarchies, cpu pipelines, out-of-order execution exist for a reason; latency is not 0 even when programming a single core.

3. Bandwidth is infinite

Caches, RAM, PCIe; every resource has a latency and throughput bottleneck.

4. The network is secure

Single boxes also shouldn’t be assumed to be secure; once compromised, anything goes: rowhammer, spectre/meltdown, etc. Even trusted sandboxes in the cloud can suffer from DMA and TEE attacks.

5. Topology doesn’t change

CPU hotplug and dynamic frequency scaling can change the topology of cores.

6. There is one administrator

Typically true, but SELinux/AppArmor/seccomp can have conflicting rules coming from different “administrators”.

7. Transport cost is zero

Everyone is building in the cloud nowadays, so not only transport has a cost; everything does. For example, given a set budget, one must decide between smaller but faster RAM or larger but slower SSD.

8. The network is homogeneous

First off, with respect to heterogeneity of the hardware itself, single boxes also aren’t homogeneous: NUMA nodes, Mac performance cores, etc.

As for the lack of interoperability, that is also not unique to distributed systems. Hardcoded OS, hardware, language, or library assumptions are all over the place.

Message-Passing vs Shared-Memory

The two fundamental ways in which distributed computing differs from single-server/machine computing are.

- No shared memory. 2. No shared clock.

Almost every problem faced in distributed systems could be traced to one of these aspects. – some overly confident hn citizen

We’ve already touched on clocks above. As for shared memory, this simple description is missing a lot of important points:

- shared memory by itself needs hardware support (CAS) in order to synchronize

- also relies on cache coherence protocols which are effectively hardware-implemented message passing algorithms

But most importantly, on a theoretical level:

- Shared memory and message passing systems have been proven dual in 1978 by Needham & Lauer

- This was at the time of os research into microkernels, so already we’re seeing that the distinction applies even inside a single box

- Even inside programming languages you can have the same distinction. Golang is famous for its CSP aphorism “Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.”

- There are (practical?) constructions of shared registers over message passing

Almost all theoretical distributed systems results have parallels in both models:

One might argue that even if message passing is used inside single machines, at large distributed scales, message passing trumps.

Shared Memory -> Message Passing Spectrum:

- true shared memory: single-core or tightly-coupled multi-core with uniform access

- NUMA shared memory: locks work but are expensive across nodes

- non-cache-coherent: locks don’t work across domains - you need message passing

- distributed memory: no shared address space at all

This is true but notice that this again is purely a performance/latency question! Coherent shared memory programming models have high coherence costs which can be avoided by using message passing systems where programmers have more control. Furthermore, CXL coherent caches over datacenter distances is also a big counter-example to the original claim!

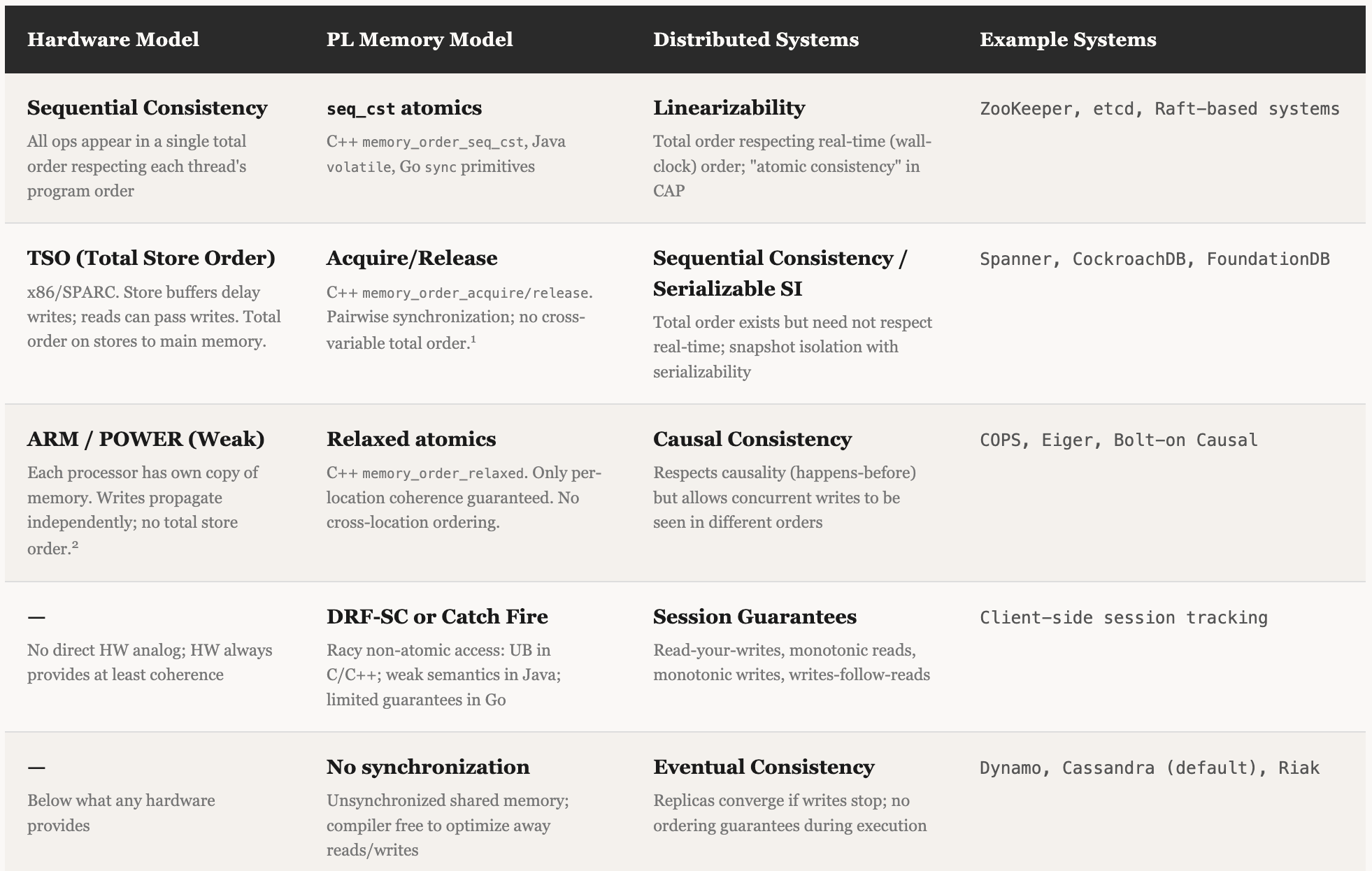

Conclusion: Consistency Models Hierarchy

In conclusion, it’s good to think holistically about the distributed systems we are building. Looking at consistency and liveness requirements should be done both at the inter- AND intra- machine scales!

There’s a fascinating relationship between consistency models at the hardware level and language/system level. And confusing to newcomers, it uses the exact same safety (consistency) nomenclature as the distributed systems literature! The liveness requirements tend to be different as HW/PL focus on latency, whereas distributed systems focus on availability. But remember that those are tightly related by the CAL theorem.

Having databases like spanner that respect strict linearizability at scale is a proof that the difference is quantitative (spanner is slow!).