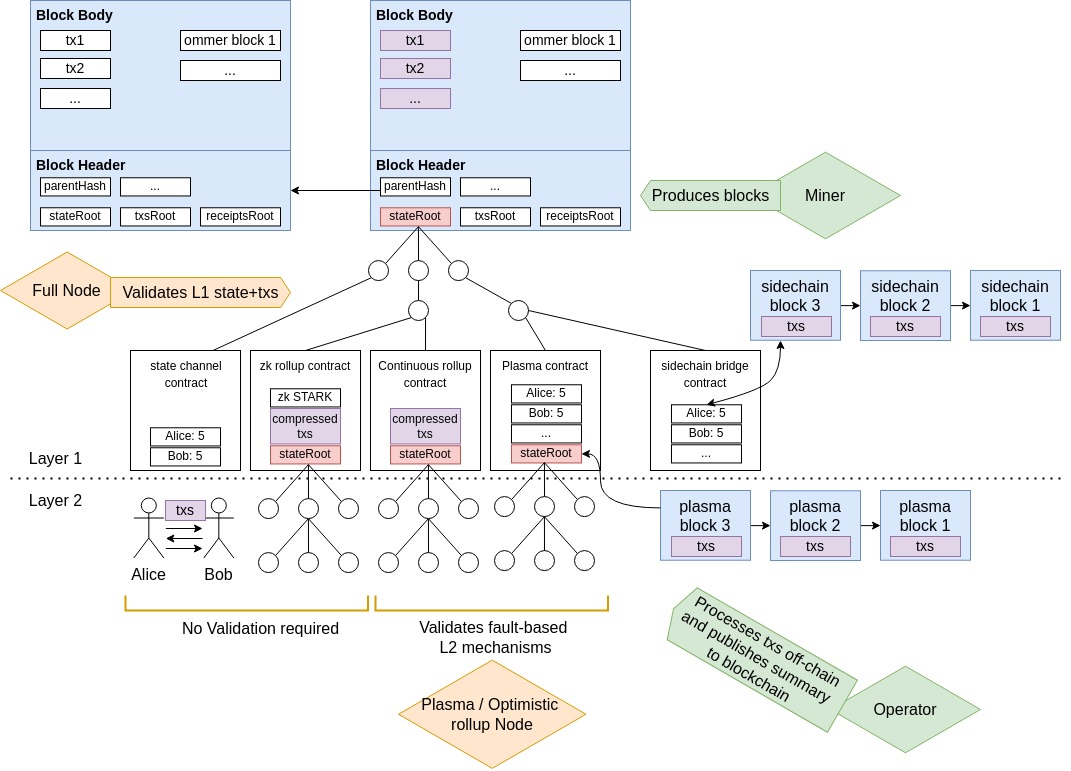

Graphical Depiction of Ethereum Scaling Solutions

Reading a few of Vitalik’s articles, you will soon realize that there are only a handful of different scaling solutions.

- Layer 1: increased block size, side chains, merged mining, sharding

- Layer 2: state channels, plasma, rollups

As a newcomer, getting a mental model of how exactly each of these differ and where they are similar can quickly become overwhelming. I have spent the last two weeks building this mental model for myself, and seeing as I was not able to find any other such visual representation of the ethereum scaling solutions space, I thought it would be a great device to share with the community. I’m also hoping to get challenged and in the process fine-tune this current model of mine.

My goal with this accompanying blog post is to describe my diagram, and present a general, visual framework for classifying and comparing the different ethereum scaling solutions, which to me has also proven useful in solidifying my understanding of blockchain data structures. We purposefully leave out many details, as there are other, more in depth articles that compare the different implementations that have started to emerge for each solution, and the companies developing them. We also leave aside sharding as it is much more involved, and harder to fit into this visual framework.

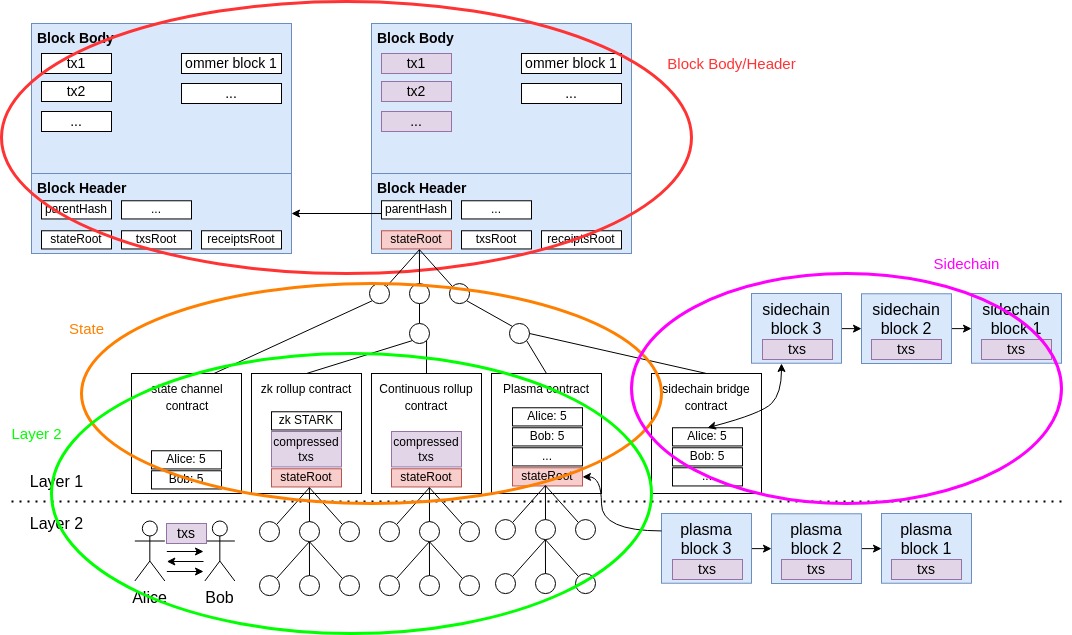

On-chain vs Off-chain data

Let’s start with a macro overview of the different parts of the diagram and how they are related to the blockchain. First of all, we often hear people using the words “onchain” and “offchain” to describe whatever they are doing on the blockchain, and contrast it with centralized exchanges or AWS or whatever other “offchain” platform. This view is quite coarse, and leaves out the entire subtleties that this article aims to elucidate.

The different parts in this diagram already hint at the fact that there exist a continuous granularity of concepts between “onchain” and “offchain”. I haven’t seen a systematic or exhaustive nomenclature for these concepts, so I’ve decided to create my own to anchor upcoming descriptions of the distinct parts.

||Block headers / body | State | Layer 2 | Sidechain | AWS, Cex, etc. ||———————————————————— chain relationship| on-chain | “on-chain” | anchored off-chain | bridged off-chain | off-chain maintained / processed by | nodes (miners, validators) | nodes (miners, validators) | operators | nodes (miners, validators) | database owner

The rest of this article delves deeper into the specifics of the original diagram, going into more details for each of the five parts.

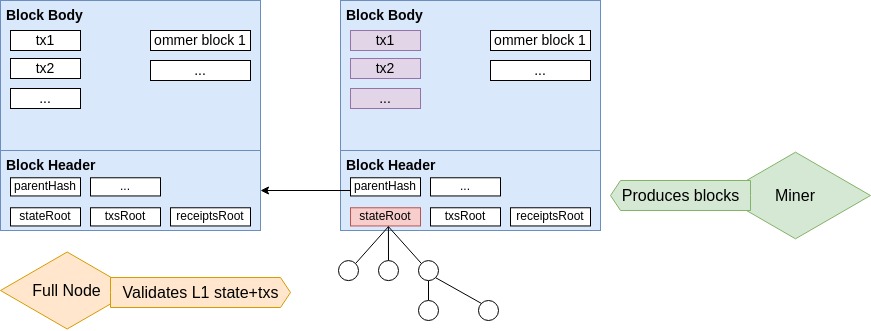

Block header/body and State

Let’s start with the top half of the diagram.

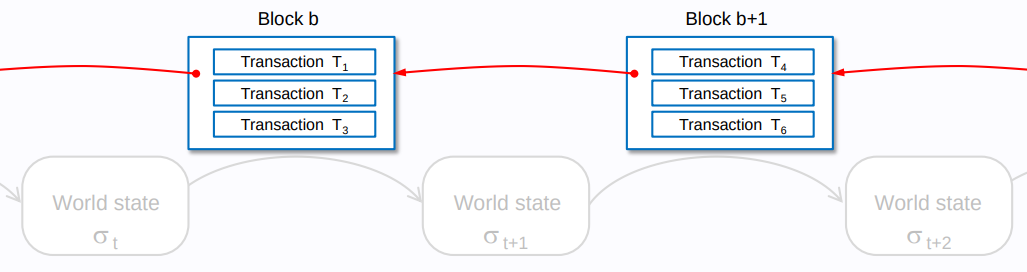

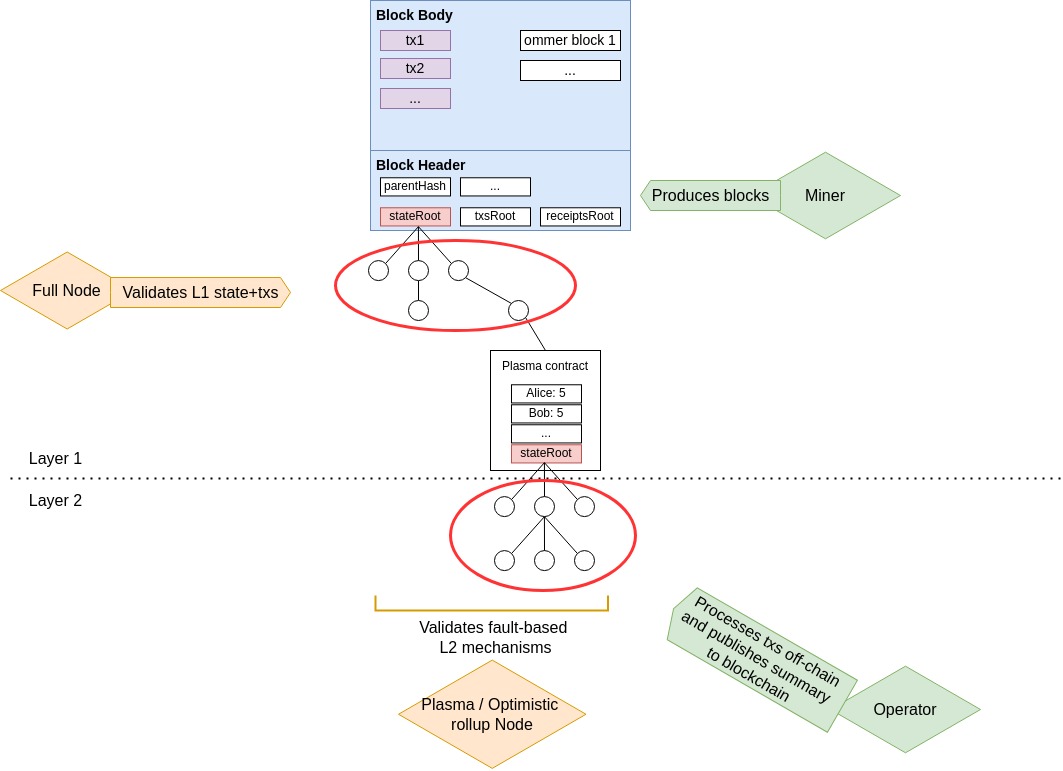

When speaking casually, people very often lump the block headers, block bodies, and state together, calling this set “the blockchain”. But formally, the “block chain” really only consists of the block headers and bodies. This is a very subtle, yet important, distinction to make. The state/storage of the blockchain (how much eth each account owns, the code inside smart contracts, etc.) isn’t explicitly stored on the blockchain; it would take up too much space and cost too much. Indeed, the state needs to be computed by each miner locally. They start from the genesis state (initial ethereum state hardcoded into ethereum clients) and recursively apply all transactions stored in the blockchain, applying the changes to their Merkle Patricia Tree database. They then compress this entire state database into a single 32-byte stateRoot Merkle hash, which is validated by full nodes (validators) that go through the exact same process of applying each and every transaction to the genesis state, and making sure that the stored stateRoot is correct. This explains our “on-chain” label in the above table: the tree anchored at stateRoot, is not actually stored on-chain!

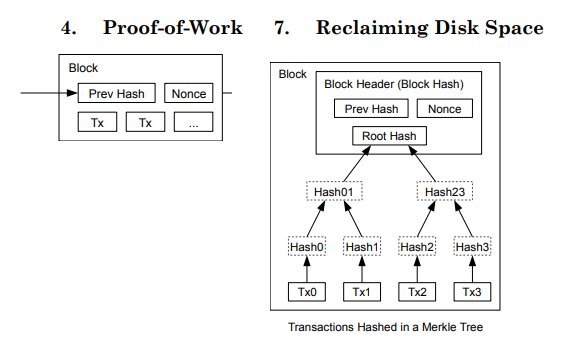

This idea of using Merkle Trees to reduce the size of the actual blockchain is not new, and falls under the famous computer science space-time tradeoff. Satoshi Nakamoto, in the bitcoin whitepaper, already used this idea to reclaim block space:

Ethereum kept this optimization transactions, and went even further, applying it to the state (which is an ethereum innovation and wasn’t present in bitcoin). The Ethereum EVM illustrated guide depicts this distinction explicitly:

They call the top chain the blockchain and the bottom chain the state chain. The yellow paper section 4.1 further expends on this:

The world state (state), is a mapping between addresses (160-bit identifiers) and account states (a data structure serialised as RLP, see Appendix B). Though not stored on the blockchain, it is assumed that the implementation will maintain this mapping in a modified Merkle Patricia tree (trie, see Appendix D). The trie requires a simple database backend that maintains a mapping of byte arrays to byte arrays; we name this underlying database the state database.

Merkle proofs are thus fundamental to blockchains, in that they permit compressing a gigantic off-chain datastructure (the world state) into a single tiny 32-byte rootHash. Publishing this rootHash on-chain establishes the legitimacy, and security, of the whole datastructure! As we will see, this exact same mechanism is used to establish the security of layer 2 solutions! Internalizing this distinction makes the distinction between “on-chain” and “off-chain” blurry, and is the reason why I prefer to use more precise graded terms.

Sidechains

Sidechains are just separate, independent blockchains, which run in parallel to Ethereum with their own sybil protection and consensus mechanism. Funds can be sent to and back from the sidechain via a two-way bridge. Most often, sidechains make use of a more centralized consensus protocol, which allows for cheaper and faster transaction processing. xDai is one such very well known ethereum sidechain. Do note however, that the tradeoff taken in order to enable faster speeds is lower security. Unlike their non-custodial cousin plasma, sidechains do not inherit the security of ethereum, and so funds lost on a sidechain are in most cases gone forever.

Interestingly, Ethereum itself can be considered a sidechain in certain cases. For example, renBTC and wrapped bitcoin (wBTC) are ways to “transfer” your bitcoins to “equivalent” erc20 tokens on ethereum, making ethereum a sidechain of bitcoin.

Off-chain

Taking sidechains to their centralized limit, we end-up with a “sidechain” consisting of a single centralized server. Sending your tokens to a centralized exchange such a coinbase is exactly this case, with the side “chain” having morphed to a side sql database.

Layer 2 solutions

Layer 2 solutions, similarly to sidechains, enable ethereum to scale to a greater number of transactions per second, but unlike sidechains, do so while inheriting the security of the underlying blockchain! The three main ones are state channels, plasma, and rollups. Our goal here is not to describe each of these in great detail, as this has already been done elsewhere, but rather to explain their relationships in the context of our main diagram.

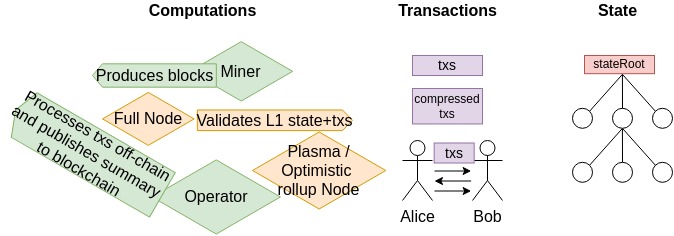

For the sake of comparison, we will narrow our discussion to where computations happen, where transactions are processed/stored, and where state is processed/stored.

Blockchains, as cool as they are, can’t yet defeat the laws of physics, and scaling solutions are no silver bullet; they’re all about tradeoffs. Understanding them requires asking the key questions: how are the transactions compressed, if at all? Where are they stored and who is guarding them safe, if not the main chain’s nodes? Who understands their format and gets to compute the state, if not the main chain’s nodes? And finally, where is this state stored and who is its new guardian?

In almost all cases, we notice that these solutions need their own separate operator and validator nodes, outside of the mainchain’s set of miners and validators.

| computation processed by | transactions location | state held by | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| state channels | signing party | kept between two parties | contained inside latest transaction | |

| plasma | plasma nodes | inside plasma blocks | only stateRoot published on chain | |

| rollups | rollup operator | on chain | maintained/validated by rollup nodes |

Of course, the whole point of scaling is to reduce transaction fees, so we also need to compare the different solutions in terms of the gas savings that they actually are able to achieve.

| what is published onchain | cost of publishing off-chain | |

|---|---|---|

| state channels | contract opening + last tx only | 0 |

| plasma | deposit + exit txs | gas fees on plasma chain |

| zk-rollups | compressed tx + zk-SNARK/STARK | gas fees charged by operator |

| optimistic rollups | compressed tx | gas fees charged by operator |

State channels

State channels are the crypto-digital equivalents of cheques, and are the simplest layer 2 solution, as they only allow transactions between two consenting parties. Instead of publishing each transaction on chain, they open up a smart contract, each deposit an initial amount, and then proceed to transact off-chain. Each such off-chain “transaction” is actually a signed message from the payer to the receiver acknowledging the new state balance of both parties. This way, the most current state (balance of each party) is kept in the latest message, and only settled on-chain when one of the two parties involved publishes it on-chain.

For example, say Alice and Bob each start with an on-chain state balance of 5 eth each. Alice buys something from Bob for 1 eth, handing him a signed message acknowledging the new balance: “Alice: 4; Bob: 6”. If she later buys another item for another token, she would then send Bob a new signed message: “Alice: 3; Bob: 7”. At any point Bob can send his latest received message to close the channel and update his and Alice’s mainchain eth balance.

Hence, for state channels, both transactions and state are kept offchain, and only the very last transaction is settled onchain, updating the chain with the current state. We leave aside the dispute resolving mechanisms as they are unimportant to this article’s main point.

Plasma

Plasma is very similar to sidechains. Vitalik has explained the difference between them better than I ever will:

Distinguishing sidechains from Plasma is simple. Plasma chains are sidechains that have a non-custodial property: if there is any error in the Plasma chain, then the error can be detected, and users can safely exit the Plasma chain and prevent the attacker from doing any lasting damage. The only cost that users suffer is that they must wait for a challenge period and pay some higher transaction fees on the (non-scalable) base chain. Regular sidechains do not have this safety property, so they are less secure. However, designing Plasma chains is in many cases much harder, and one could argue that for many low-value applications the security is not worth the added complexity.

Apart from this fine explanation comparing plasma to sidechains, its also important to stay inline with this article’s main theme and highly the distinction, or rather similarity, between the mainchain’s stateRoot and the plasma stateRoot.

This summary diagram gets to the essence of the distinction: the mainchain stateTrie is processed by mainchain miners/validators, whereas the plasma stateTrie is processed by plasma operators/validators! Plasma thus achieves scale by having fewer operators (compared to mainchain miners), and using a less costly consensus protocol. Full decentralization, as exemplified by the mainchain, is extremely costly, because all nodes are forced to compute the exact same computation, for every single transaction processed. This achieves maximal security, but at an extreme, often wasteful, cost. Layer 2 solutions aim to achieve the perfect tradeoff: centralizing block production to achieve faster speeds, but keeping the key block validation process fully decentralized!

Rollups

Rollups are now all the rage, and have been lauded as the current most important way to scale ethereum. Comparing rollup contracts with plasma contracts in our main diagram, we immediately notice the difference: rollups have their transactions posted inside the smart contract, onchain! How then can they achieve scalability? Simply put, by another compression technique: the transactions that they post to the mainchain are very compressed, and don’t even include a signature.

Continuing on the discussion in the last paragraph of the plasma section, rollups fully centralize block production: unlike plasma, they don’t form a chain of their own, and so don’t need “miners” like plasma does, they rely on a single centralized producer. And this producer is kept in check by a multitude of decentralized validator nodes.

Rollups come in two flavors. Optimistic rollups use a fraud proof mechanism to secure their users, not unlike plasma, whereas zk-rollups use a validity proof mechanism to achieve the same result. Optimistic rollups are simpler, but unfortunately don’t achieve immediate finality. zk-rollups, on the other hand, achieve immediate finality, but rely on extremely complicated mathematical objects that would require dozens of blog posts to explain on their own. We leave these details to future articles.

Conclusion

I’ve shared my current mental model of the ethereum blockchain and its different scaling architectures. My only hope at this point is for this to spark interesting discussions and debate, and to be able to learn from more experienced developers. So please do write to me regarding improvements I could bring to this framework, and let’s all keep learning.